In February 2020, Irish chemist Claire Murray provoked me. She spoke clearly and passionately at one of the last professional meetings I went to that was unaffected by lockdowns and social distancing. It launched a book called ‘Women in Their Element’, telling the often-overlooked stories of female scientists involved in filling in the periodic table of chemical elements. And it has changed how I work ever since.

In her talk Claire went beyond recapping her chapter, jointly written with Jess Wade, the pioneering activist on gender bias in science, on discoverers of the superheavy elements at the bottom of the periodic table. She also revealed the biases that have prevented women from being as successful in science as they should be. These include sexism, harassment, and stereotypes that women shouldn’t be scientists. Altogether this leads to a ‘leaky pipeline’, where fewer female scientists progress to more senior levels than male ones. Similar leaky pipeline issues also face Black, Asian and other ethnic minority scientists.

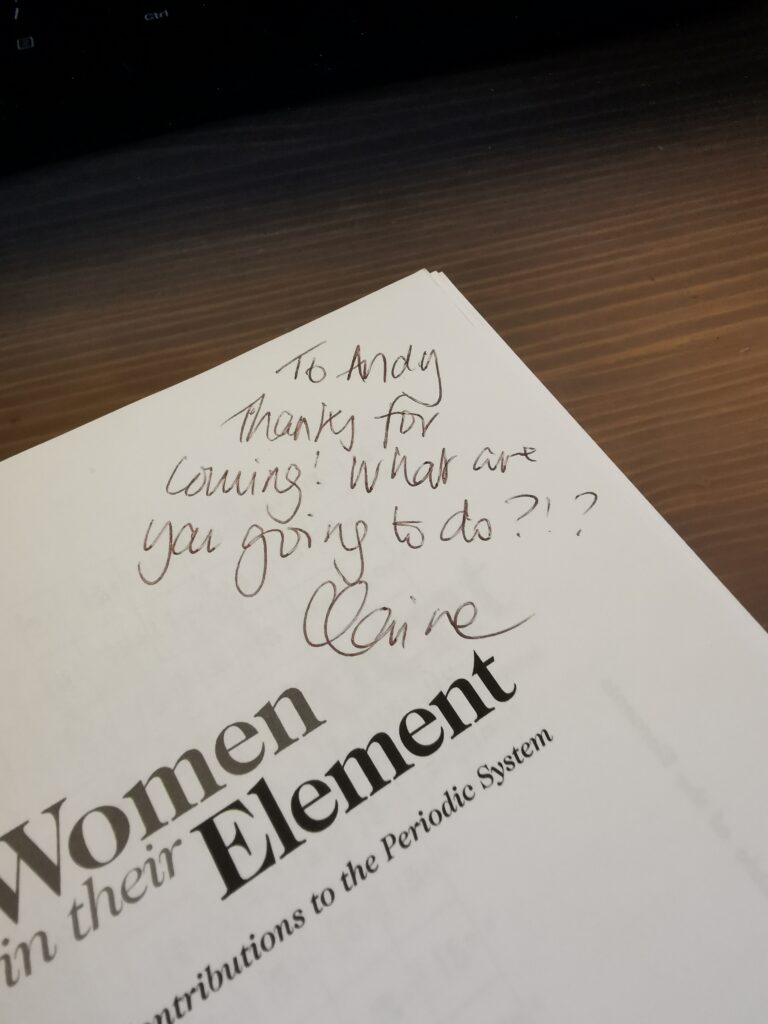

“We have allowed science to be the lone male white genius for too long,” Claire said. She ended by challenging us. “What can we do?” she asked. “How can we measure change? Who is responsible?” and finally, “What are you going to do?” When Claire signed my copy of the book, she repeated that provocation. “What are you going to do?”, she wrote.

Tracking balances

I decided that I would seek to help challenge the imbalances by following the example of another great inspiration, Pulitzer-prize winning Atlantic science writer Ed Yong. Following the example of his colleague Adrienne LaFrance, he audited his own stories for gender bias. Around a quarter of the sources from his 23 pieces from 2016 were women. Around a third quoted no women at all. By 2018 around 50% of Ed’s sources were women, and only 7% of his stories had no female voices at all.

Through 2020 I tracked my own stories, both for gender and ethnicity – but the pandemic overwhelmed my thoughts. At the book launch, I had just written my first article about the coronavirus that would come to dominate our lives. Amid the chaos, I didn’t manage to analyse my data last year, but I continued tracking. And this year, I did the analysis.

In both 2020 and 2021 my gender balance has been similar to Ed Yong’s in 2016 – 24% of my sources were women in each year. The proportion of articles with no female sources at all went up from 29% of 48 stories in 2020 to 45% of 33 stories in 2021.

Progress on ethnic balance has been slightly more encouraging. 83% of my sources were white in 2020, which fell to 76% in 2021. The proportion of articles with only white sources fell from 48% in 2020 to 38% in 2021.

All of which I found a bit shocking, as I try hard for balance in my articles. But after a bit of sanity-checking it’s less surprising.

A world that could be

In March 2021, the UK’s Royal Society analysed the number of researchers eligible for its fellowship programmes. 42% of them were female, and 29% came from minority ethnic backgrounds. However, gender balance is worse in the subjects that I usually cover, roughly considered physical sciences, at just 27% women. In engineering and physics that number is just 23%. In the biological sciences, which Ed Yong typically covers, 57% of researchers eligible for Royal Society fellowships are women. So, may be easier for him to reach 50% women scientists in his articles.

But I don’t just write for UK publications or speak to UK scientists. Looking worldwide just 30% of scientists are female, according to UNESCO’s Women In Science 2019 report. But in the US, about half are women, while around 30% of scientists are from ethnic minorities, says a report from the Pew Research Center in April 2021. There appear to be more women in physical sciences in the US than in the UK, around 40% of the total workforce.

While I could argue that I am not greatly underrepresenting women or minority ethnicities, considering that I mainly cover physical sciences, I am not entirely happy. For 2022, I will strive further to increase the proportion of scientists from these groups in my coverage. Why is that important? Isn’t it good enough to reflect the way things are? Not in my opinion. I am with Ed Yong on this when he says: “…I don’t buy that journalism should act simply as society’s mirror. Yes, it tells us about the world as it is, but it also pushes us toward a world that could be.”

What else is going on in my life?

In early December, Education in Chemistry published my most recent piece on ‘meat analogues’, food that is like meat, but with less involvement from animals!

I am chair of the Association of British Science Writers (ABSW). On January 27 we will be having our annual ‘Award Lecture’ on the future of science journalism, with winners from 2021’s awards. The speakers with be Tom Chivers from Unherd, British Science Journalist of the Year, and Anjana Ahuja, columnist at the Financial Times, winner of Opinion Piece or Editorial of the Year. You can register for the online lecture here. From early January you will also be able to enter the ABSW awards 2022 here. Get in touch if you would like to get involved with what the ABSW does.

I am also editor-in-chief at science news aggregator ScienceSeeker. Read our latest choices of the best recent science posts here and get in touch if you might like to get involved.

In addition, I am a director at Exeter Community Energy (ECOE) – if you want to do something about climate change, I highly recommend seeking out your local community energy group. We also help fight fuel poverty, as there is a big overlap in reducing people’s fuel bills and cutting their emissions. We are currently raising money for our Winter Warmth campaign to help vulnerable residents. Please donate here. Get in touch if you would like to get involved with what ECOE does.

To keep in touch with all my posts and other news, please sign up for email updates below: